Religion: The Ultimate Art Form

A lecture first delivered at St George’s Church,

Campden Hill, London, on 4 October 2016

Thank you for coming to listen to a talk on a theme, which on the face of it would have been enough some seven centuries ago to have the speaker bound at the stake ready for burning. When Father James heard of my flash of perception of ‘religion – the ultimate art form’ from a member of his flock, a great friend of mine, he daringly invited me to be one the lecturers in the series Exploring Faith through Art. Thank you, Fr James. For my flash of perception was somewhat à côté.

He and I had a brief discussion on the title: Religion is the Ultimate Art Form/ Religion as the Ultimate Art Form. He left me to learn from the first printed notice that it was to be neither: The colon came to the rescue – Religion: The Ultimate Art Form. Since then I have seen the intrusion of yet more cautious punctuation: a concluding question mark. But my perception does not leave me with a question. I intend to present a thesis precisely declaring that Religion is the ultimate art form.

Having begun with semantics I should point out that my word ‘religion’ is not the same as the series’ word ‘faith’. This is a point to which we shall return.

The ultimate art form: that is what I intend to demonstrate. Yet you may be surprised by the manner of my thinking and my line of argument, which will reverse any hint of blasphemy. My theme is ‘religion’ in the context of art: not exclusively Christianity. Yet I, like you, am a Christian by conviction and observance, and we shall this evening close in upon the uniqueness of the Christian religion in my assertion of Ultimacy.

Where did religion originate?

Let us regard ourselves. Man is but Man on his one-off planet of an infinite (and eternal) universe – a single (and singular) species of mortal animal, which astonishingly and uniquely has evolved to the attainment of consciousness. By consciousness he came to recognize, and hence must recognize, the mystery of his time-tagged presence within the one-ness of all things, ‘visible and invisible’. Our critical sentence here occurs in Verse 11 of chapter 3 of Genesis: It is the voice of God, picked up by Adam: ‘Who told you that thou wast naked?’ Consciousness has arrived. From that moment Man must probe and express the mystery of his existence by means of any fragment of knowledge and fleeting expression he can attain to.

He cannot but. Given the terrifying isolation that consciousness has brought him, he must so probe and ‘express’. He clothes himself or at least his reproductive parts by means of his own ingenuity, his own artifice, his art, with what is to hand. He alone must rise to the grandeur of his task of probing-by-expressing.

Dear Friends, permit me a little biography, to serve as credentials of some of the things I wish to say, and to reveal what has impelled some of my thinking up to this point in my life.

A few weeks out of my teens, I was living for a little while with the hunter-gatherer aborigines of the Malayan jungle, or in the language of a modern generation presuming to protect jungle from world-wide devastation, the ‘Rainforest’. Four years later, then aged 24, I was living for several months in the Ruwenzori Mountains on the borderland between what was then Britain’s Uganda and Belgium’s Congo. I was among a people clad in bark-cloth, goat-hide and monkey skins in what was effectively uncolonised Bantu Africa. Immediately at the foot of those amazing mountains, Congo-side, in the vast Ituri forest, dwelt Bambuti pygmies, central Africa’s own hunter-gatherer aborigines. So from early on I have had some familiarity with, and an immersion into, the manner of life of homo sapiens in his evolutionary trajectory. I shall be back among those mountains next week.

Now – next point – wherever my subsequent career has taken me (as foreign correspondent writing from, and about, 128 countries (some of them frequently), in publishing in the Islamic world and in London, in home politics and familyhood) the urge to write from out of the centre of a life which has seen so much has never let me go. I, personally, remain cursed or blessed by the call, that vocation, to probe and express, as a writer. So I for better or for worse am a creative man, an artist. I am in the business of expressing my probing as the written word..

Like you, I am the product of a civilization of Judaeo-Christian roots, living in a period of unrelenting secular challenge stemming from popular science, and fed by moral licence, and growing out of the enthronement of Reason. One may date that, I daresay, from Descartes in the early 17th Century and Kant half a century on; and subsequently through Hobbes and Hume, Paine, Darwin, Marx and Freud to the fashionable secularists or atheists of our time. Such an erratic sequence of figures is matched by the astronomers and cosmologists from Copernicus and Kepler to today’s space probers of our own lifetime.

Temperament has had me making my own rules in life, my own exploration and my own mistakes; and as I have pushed along, my engagement with the core of Christianity embedded in the ‘Catholic and Apostolic Church’ (in credal terms) has drawn me into ever keener conviction of Christianity’s Truth – Truth with a capital T. This doctrine, this rite, this narrative, this imagery and the practice of this core Christianity, do not date, I must stress, from the other day – from the bit between17th century and today I have just referred to – but from two millennia ago and the presence on earth of Jesus Christ; and indeed from some two or more millennia earlier and at least one prober’s and expresser’s unprecedented recognition of a single, immortal, omnipotent creator-God that saw His own image in Man. We call that the Abramic vision, a vision of God which demanded of Man all that he supposed himself to be comprised, including Abraham’s sole, adored and rightful son and heir.

That was not the beginning of religion as such – of man’s unquenchable urge to probe and express the mystery of his presence on his ‘infinitely insignificant planet’ whose human inhabitants, even so, are incapable of counting themselves as anything less than of infinite significance.

When do we find the first hints of Man’s awareness of himself as of timed mortality amid the master reality of timelessness and infinite space?

Out of my ragbag of accumulated knowledge of prehistory, I draw a tiny clue from a species of hominid not belonging to the phylum of homo sapiens, but to our Neanderthal cousins. They, as you know, cohabited Europe and Asia alongside Aurignacian Man (who is us) for some tens of thousands of years up to around 40,000 years ago. Indeed they survived as a distinct species, as we have recently discovered, in Gibraltar as recently as 11,000 years ago. Neanderthals differed from us physiologically and brain size (theirs were bigger), the thickness of the skull and the articulation of the head and spinal column, the emphatic brow ridge, and their relatively primitive stone tool culture, and – from physical evidence – linguistic capability. They had command of fire, and – crucially – this is my contextual point: they honoured their dead with a ritual burial and would sometimes return to the skeletons of their departed fellows to stain the bones with red ochre. That implicit investment with the properties of lifeblood and the mode of survival transcending mortality do not constitute art; but we are getting warmer.

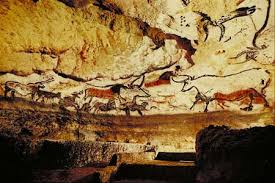

The Neanderthals were outhunted by homo sapiens and possibly ethnically cleansed. Some of you may have read William Golding’s novel, The Inheritors, written from the Neanderthal point of view on the theme of their encroachment by the superior hominids. They mostly did not survive the pretty swift onset of the last Ice Age of some 40,000 years ago. But let us cut, dramatically, to that moment in 1867, when the little daughter of the owner of the estate of Altamira in north-western Spain came dashing from the mouth of the complex cave on the family’s property crying ‘Toros, Toros’. As the child’s eyes had grown accustomed to the gloom, she had found herself confronted by vivid images of stampeding auroch bulls rendered on the cave wall in lively colours by their family’s late ice-age upper-Palaeolithic predecessors on the territory some 18,000 years previously.

That moment in 1867 marks the start of the discovery of breath-taking parietal art by our Stone Age ancestors across a great swathe of northern Spain and southern France, outstandingly at Lascaux and the Dordogne, and in the Pyrenees at Niaux, which I have seen myself. This is art of dazzling attainment, by any measure, brilliantly depicted in form and colour, in animation of power, aggression and docility – the entire gamut of large mammals with which hunting and hunted Man shared his space: bison, aurochs, the great bear (now extinct), ibex, antelope and lions. As you very likely know, these images were painted on surfaces that are often compliant with the rock itself, and often on remote slabs of the cave’s rock-face of wilfully selected inaccessibility, as if shrines conducive to spiritual endowment. The caves are invariably ramified, lofty, deep, treacherous underfoot and usually of difficulty of entry from without and hence with little or no natural light. They were negotiated by men carrying moss-lamps fuelled by animal fat and providing the meanest arc of light. As for the painting themselves, each with its unerring and deceptive spontaneity, they got their colour by powdered pigment blown by the artist’s mouth across a multitude of tiny holes that had been peppered into the surface of the rock with pointed flints, preserving the colour to this very day. Frequently images were superimposed, one upon another, in apparent random. Yet each was reverentially executed in response, I venture, to the gratuitous beauty of the beasts portrayed, and done in inferential thanksgiving. (I mean no less than what I say.) This beautiful art spanned some 4 millennia. Man’s first essay at pictorial art was unquestionably religious in function and intent. Each setting of these petroglyphs was surely a site of prolonged ritual drumming, dance and chant, presided over by a shaman speaking with the voice of the spirit-world above, himself stimulated by prolonged rhythmic movement, rapid shallow breathing, and quite possibly a herbal hallucinogen.

Now, I have witnessed this in person, indeed participated 66 years ago in the jungle of peninsular Malaysia, among the lower strata Temiar, lasting three nights and two days. And also present, at one remove, at comparable spirit-singing among the Bakonzo of Ruwenzori on the Congo-Uganda border, where the art involved is drumming, dance, and invocation. Shamanism is still practised in our world today, to my knowledge in Kazakhstan and Sinkiang; and artificially revived in California. So far as I know, it has been conducive of pictorial art only in upper-Palaeolithic Europe. There its purpose might well have been to invoke the spirits for success in the hunt and protection from predators, and for boosting Man’s fertility and the libido. It is pagan art, but it is religious. Pagans have religions, to be sure.

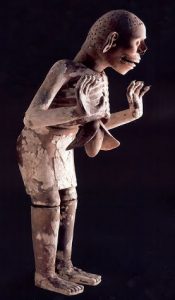

I have dwelt on this to assert the fact that this first-ever art is invariably religious, and to show how that remnant of Man’s primality in our world of today still lives all the while and every day beholden to a spiritual reality. For the hunter-gatherer of our own time the environment he occupies is his universe, no less. That mystically created universe rules, sustains, nurtures and protects him. With it he intimately collaborates from birth to death. He venerates it. To that universe of today’s deep tropical forests, Man devotes the firstfruit of his own creative and devotional gifts in image and creative idea. I have with me two samples of such firstfruit, of primal art, which I myself have collected in what you would think of as remote places in the Africa of, respectively, 62 years ago for the ivory sculpture, and 56 years in the case of the wooden carving. Neither was made for the visitor or outsider; neither were idols as such (as an object made to stand in place of the Divine); yet both were objects of ritual veneration.

The ivory – please handle if you will – is from Azande territory in what was then Oubangui-Shari of l’Afrique Equatoriale Française; the wooden nkisi is a fetish of the lower Congo. Do not handle the nkisi, because I want to preserve the grass skirt that has survived this half-century and more, but do gaze upon its formidable strength and inwardness. Take note of the emphatic navel, which is the sculptor’s assertion of Man’s potentially infinite perpetuity, his claim on immortality. As to the Azande ivory, you and I are the crouching figure in abject subservience to the dominant spirit, benign or malign, in unrelenting control o ours our fate and fortune. Both are items of religious art among people of relative primality who create no art but that which carries a religious function. For among both such communities the governance of the realm of the spirits is, or was, paramount and pervasive, day in, day out.

The ivory – please handle if you will – is from Azande territory in what was then Oubangui-Shari of l’Afrique Equatoriale Française; the wooden nkisi is a fetish of the lower Congo. Do not handle the nkisi, because I want to preserve the grass skirt that has survived this half-century and more, but do gaze upon its formidable strength and inwardness. Take note of the emphatic navel, which is the sculptor’s assertion of Man’s potentially infinite perpetuity, his claim on immortality. As to the Azande ivory, you and I are the crouching figure in abject subservience to the dominant spirit, benign or malign, in unrelenting control o ours our fate and fortune. Both are items of religious art among people of relative primality who create no art but that which carries a religious function. For among both such communities the governance of the realm of the spirits is, or was, paramount and pervasive, day in, day out.

Does such paramountcy strike any cord, any echo, in the Christian heart? What does George Herbert tell us, writing in about 1640?

Does such paramountcy strike any cord, any echo, in the Christian heart? What does George Herbert tell us, writing in about 1640?

Teach me my God and King/ In all things the to see,/And what I do in anything/ To do it as for Thee.

The innate urge to create, I contend, irresistible and spontaneous, stems from Man’s requirement to rise to the grandeur of the task of probing that wholeness of all things, seen and unseen, to which he knows his being belongs. Such is the pith of his motive whether or not he is aware of it, and whatever the overt subject or model or theme of any specific work.

(Let us be clear that the word whole is the same word as ‘holy’: we repeat it no less that 22 times in a Communion service.) What that urge generates is, in primal Man, the sole expression of what we name art. The form that art takes, as I have indicated, straddles the entire spectrum of possibilities for Man: song, dance, drumming; the plastic arts of sculpture, by moulding, carving, founding of metal or glass, the firing of ceramics; picture making by painting, drawing, engraving and incising; body painting and tattooing and ornamentation of the body; regalia-making; even cooking. And of course the spoken or the written word. (I shall come to the Word of God.)

All skills essential to Man’s survival are harnessed and honed to this other endeavour to make art, which is economically worthless, and functionally useless, yet it is has summoned in Man the highest gifts and apogee of his talents and so rewarding him, inwardly, ineffably.

The art thus rises from the crafts, that is to say the techniques; and those very crafts bear within them the reflexion of the holiness of artistic endeavour. The woodworker – joiner, carpenter – may be exclusively occupied by the production of useful objects, as surely was the Nazareth workshop of Joseph and his sons, including the eldest, Jesus: lintels and jambs, doors and benches, coffins and chests, hafts and ploughs and the bushels and yokes which crop up in the teaching of Jesus. Which of you knows of a skilled joiner who does not love wood, revere wood? Much the same for the potter, the weaver, the smithy and the foundryman.

And the musician? I am not contending there was no secular engagement for the music maker in primal society. And yet, in my personal experience, man in the primal mode makes music initially in ritual and in meditation. (Let us note in passing the centrality of meditation in Man’s spiritual life; literally so – his self-centring into his isolation his nothingness, the ‘still point of the turning world’ as T. S. Eliot expressed it in poetic art.) Observe how in Africa, in the tribal state a man or a boy (it is always the male) will ‘pray’ with the drum, meditatively on his own. Yet the drum in its turn will become the rhythmic master of the collective dance for any funeral or propitiation of the spiritual world. Overhear the tribal herdsman, alone among the family’s goats or sheep, drifting off into his melisma, who that night may become the sustainer of the chant and vocal improviser in collective communion with the spirit world of the locality.

See how craft therefore responds to the whole in both directions (think of the woodworker and that nkisi) – to that whole which is of nature, of the given, intuitively, in the sanctity of its givenness; and in the other direction to the whole of that which is craved by heart and soul, confronted by the mystery of Man’s mortality amid the eternal. Look back on that navel (of the nkisi).

So we see how thinking Man evolved into his civilizations and his cosmological theories always in thrall to whatever might be comprehended of the incomprehensible. Nothing was strictly secular, there was no natural duality. There was misfortune and good fortune, suffering and delight, curse and blessing: yet all derived from, was rooted in, the holy. Contrast and compare the pharaonic gods of the riverine civilizations – our planet’s first – of the Nile, the Indus, the Yellow River and Mesopotamia; the Buddhists’ annulment of the created world’s validity in deference to a godless nirvana; the vast metaphor of myth and philosophic discourse of the Sanskrit Bhagavad Gita and the Mahabaratha; and far away the unassuageable deity of Mexico’s Mayans and Aztecs (pictured).

And now, closer to our own inheritance, the dysfunctional junta on Mount Olympus of the ancient Greeks to whom we owe that formidable legacy of creative art in narrative, poetic myth, drama, architecture, and sculpture. You will know as well as I that the presentations of the amphitheatres of the work of Aeschylus or Euripides or Sophocles or Aristophanes were always a religious event, an artistic offering to the gods, by virtue of their being works of art, and hence of inspiration: ‘of the spirit’, the psyche. You may recall the occasion when the bossy sons of Sophocles (the playwright well into his nineties) petitioned the law court in Athens for them to take over papa’s affairs on the grounds of his incapability. Sophocles challenged the petition. He entered the court carrying the manuscript on vellum, wrapped in a cloth, of his latest play and slapped it down on the judge’s table as evidence he still had all his marbles. It was, naturally, a masterpiece, Oedipus at Colonus. The court found for Sophocles: a work of creative art, of sacred inspiration, trumped the sons’ managerial contention.

No less products of the divine spirit at work in Man were the sculptures of Phydias and his fellows, and no doubt the paintings on surfaces of stone in

ancient Greece which have not survived. Likewise the Olympic Games were staged as celebration of thanksgiving to the Gods for the aesthetics of physical Man, pinnacle of the gods’ creativity. The Parthenon was in the first place a religious statement in architecture dedicated to the gods, a statement we can hear today.

Such was the natural stance, the mindset of Man of the time of the birth of Jesus of Nazareth. And he himself was self-acknowledged as recipient of the legacy of the most sophisticated religion then known to man. Judaism was held close to the chest, within its tight ethnic exclusivity, even possessiveness, albeit enshrined in works of literature of surpassing authority, such that three millennia later they still resound across our civilisation above the cacophony of its attention-seekers.

We here know our bibles, in something of the way Jesus knew his Torah. The artistic genius of the creators of triple-authored Isaiah, the Psalms of David and Asaph in their astonishing poetic invocation of intimacy and praise, sorrow and joy, of wonder, courage and love; the wholing ecstasy of the Song of Songs; the blazing autobiography of Job, for Job wrote Job (make no mistake); the magisterial detachment of Ecclesiastes, the poetic gift of Hosea, the rampaging imagination of Ezekiel, the narrative mastery of Daniel – all works of art for a people for whose raison d’être was their faith, their pharisaically treasured, even hoarded, penetration of the mystery inherited from the figure of Moses and his prophetic, poetic successors.

Then Jesus came, to make of it all – that vast endeavour, enshrined in art as, supremely, the written word – an incontrovertible interpretation of redemptive sense. In his own terminology, he came to ‘fulfil the law’. All that had gone before, all that vast creative attainment of mankind that had survived in words, myth, narrative and artefact, and in evanescent music, was revealed as love, the overriding and overwhelming paradox of fulfilment in self-loss or, in the end, self-sacrifice. There was to lie revealed the true interpretation of all that had gone before and that would follow, in humankind’s endeavour to probe and express the mystery of the gift of life. It was God’s love, awaiting Man’s response. The Jews of Jesus’ time half-knew it; its supremacy was declared in Deuteronomy, for the heart, the mind, the soul; yet it awaited, agonisingly, Jesus himself to live it and exemplify it, to the point of death, the nullity of the Cross… and resurrection.

Then Jesus came, to make of it all – that vast endeavour, enshrined in art as, supremely, the written word – an incontrovertible interpretation of redemptive sense. In his own terminology, he came to ‘fulfil the law’. All that had gone before, all that vast creative attainment of mankind that had survived in words, myth, narrative and artefact, and in evanescent music, was revealed as love, the overriding and overwhelming paradox of fulfilment in self-loss or, in the end, self-sacrifice. There was to lie revealed the true interpretation of all that had gone before and that would follow, in humankind’s endeavour to probe and express the mystery of the gift of life. It was God’s love, awaiting Man’s response. The Jews of Jesus’ time half-knew it; its supremacy was declared in Deuteronomy, for the heart, the mind, the soul; yet it awaited, agonisingly, Jesus himself to live it and exemplify it, to the point of death, the nullity of the Cross… and resurrection.

Jesus lived it and spoke it, preached it in the flow of his own medium of creative art, of parable and simile, drawing from the material world immediately to hand, upon such as which all art must draw for its making: the painter for his subjects and his colours, the musician for his melodies and reed and strings, the storyteller for his narratives, the sculptor for his models and the wood or stone or clay to render them anew; the lover for his sonnet or the mourner for his loss. Jesus did not make a church, or indeed a ‘religion’: that pattern and practice of worship to bind and enthral his devotees in a structure of doctrine, liturgy, ritual and discipline, and in due course hierarchy and edifice. That was the art form for the devotees themselves to devise and refine; inspired, literally so through grace, by the initiator of the faith, Jesus of Nazareth. His Truth, like sacred fire in a pot, was in the oral tradition of those who had known him and heard him, apostles and disciples, the immediate Epistles of Paul and Peter and John, the late-hour writings of the four evangelists, the summation of the author of Hebrews, and the final apocalypse of John of Patmos. The subsequent sustained collective creative endeavour of religion took, as you know, the better part of four centuries for the working church, centred upon Rome, harnessing the inspiration of belief in Christ, to refine its ritual art to provide for worship, and so to root that faith as Truth in the heart of all who sought the presence of God, whether peasant or sage, humble or sophisticate, illiterate or scholar.

By the heart’s conviction of its final Truth this new religion was to stand or fall, cleansed of heresy – Aryan, Pelagian, Nestorian, whatever – each passionately confronted and thrust aside. The religion was to make for the transcendence of thought and emotion; and for the elevation of that to be worshipped in faith to an authority deriving ultimately from reverential love. The norm and form of worship thus ordained must make for the supervention of not only the analysis that thinking induces but supervention also of the engagement of sentiment, of desire, of any notion of possession; and so bring the worshipper to the negation of negation, the critical polarity of nothingness and all.

To rehearse the convolutions and schisms of that early church and subsequent ecclesiastic refinement will distract from the thrust of this talk except as evidence of Man at work; Man, creatively inspired, to render transmissible his perceived Truth to the greater fellowship of all comers, just as for any artist truly inspired and driven, ready to lose himself in what he cannot but strive to offer. Here is the art form of man’s faith as religion. Just such artistic endeavour, I daresay, was at work in the church’s early saintly contributors to religion-making, of whom one might cite Polycarp, Ignatius of Antioch, Clement, and Augustine of Hippo. You will fill the gaps for me. This religious art form of the Christian faith was never to cease being worked on, whatever its doctrinal formulations as in Nicea (352) or Calcedon (451). The religion would evolve its own modes of probing and expressing out of the core faith in the incarnate God, as among the desert Fathers exemplified by Anthony, or by the scriptural master Jerome, the sublime Benedict of the sixth century who set off the Church’s vital monastic traditions, or by the flowering of the Eastern Church (with its iconography, exemplified by Rublev); or by Hilda of Whitby, the uniter; Francis; Hildegard of Bingen, Thomas Aquinas, Meister Eckhart, the daring challengers of corrupted Rome like Wycliffe and Huss, Zwingli and Calvin, the mighty Luther, Ignatius of Loyala, Teresa of Avila; Knox, Fox and Wesley of our own shores. Let us see them all as creative contributors to the art form of Christian religion, which brings you and me to this church tonight and informs our faith.

Look, then, how this art of worship at its height makes for such awe in the manner of devotion, such as I have already half-defined as ‘reverential love’, that will ‘take the breath away’, ‘weaken in the knees’, ‘drown the ears and blind the senses’. Have we not identically been brought such experience, let me put it to you, devoid of any doctrinal context or purport, by the work of all true masters of the creative art – by, say, Beethoven in his Seventh Symphony, building from the opening bars of the slow movement to accumulative mind-blowing declaration of musical Truth of the fourth movement, by which the listener is no less than ravished as by an act of love on the part of the beloved.. Or, say, by Maurice Ravel invoking by orchestral genius in his evocation of the union of Daphnis and Chloë. Or by Brahms, the declared agnostic whose Requiem is in my view of higher spiritual elevation than that of the church-going Verdi.

And here we note the supreme authority, repeatedly in our culture, of our Christian religion and the creative masters in triumphant combination. Do you remember how it was reported by Handel’s housekeeper, at his London home – how she encountered the master emerging from his music room one noonday with tears pouring down his cheeks? She learned that he had just written down on paper the Hallelujah Chorus. And do you not recall how Edward Elgar, whose inky pen was still wet with his scoring of the final bars of The Dream of Gerontius, to Newman’s poem, scribbling on his manuscript paper in the wonder of his inspiration, This is the best of me.

I have not yet – and I have no time – to bring back to you the testimony of comparable creative spirits in their ‘probing and expressing’ in the pictorial and plastic arts and in architecture: how often and vitally they endow us in the harnessing of their gifts to the Christian message. Music may be my own most frequented mistress, yet on the instant we can all share that entire sweep of Renaissance art, oh – from Giotto and Cimabue, to Michelangelo and Leonardo, Fra Angelico, Ghiberti, Donatello, Raphael, Masaccio, Titian … El Greco. And then: which of you, like me, has not stood in wonderment before Rembrandt’s The Return of the Prodigal Son in the Hermitage at St Petersburg? Or before The Adoration of the Magi by the Dutch master’s older Flemish contemporary Rubens, fronting the high altar at King’s College chapel in Cambridge? Which of you might have gazed upon the altar-pieces and screens in Strasbourg, say, or Ulm, carved in wood by Tilman Riemenschneider at that late mediaeval period? How the Christian narrative has captivated the creative soul! And what was the force and fount of that captivation? The divinity of love! [look back to the Deposition already pictured].

Our other lecturers in this series will delve into their chosen regions or exponents of Christian art – and that art should properly embrace for Christianity the vast gamut of non-scriptural literature known among us here, which has informed mankind across the globe and down the ages. My own familiarities have me flitting from creative inspiration of Dante Alighieri of the Divine Comedy to Petrarch, the gift-of-life embracer, to John of the Cross as poet, to our John Milton and the deathless English contributions of Donne, Herbert, Traherne, Hopkins; and not much less the novelists: whom shall we snatch from the air? – Dostoyevsky, Mauriac, Solzhenitsyn, Shusaku Endo, Greene…

Christian art is not the nub of my thesis. My thesis is the identity of Man’s requirement to make religion and Man’s requirement to make art. Let us be aware, however, of the mastering appeal to the mind and soul in the creatively endowed of the Christian faith, supremely exemplified in the Christian narrative. It is manifestly irresistible to this very day. The brightest stars in the English poetic firmament of our own era are in the Christian fold, or alive to Christian truth: Eliot, say, or Auden; or Geoffrey Hill or R S Thomas whom I have personally known in North Wales; or the sculptor Henry Moore, the painter Stanley Spencer; composers from Britten to Tavener to James MacMillan.

That identity, that impulse, to worship and to make art spring from one and the same inner demand of the spirit, the psyche. Both are probing the Truth of the phenomenon of creation. The one produces religion in the multiple variety I have touched on, the other the entire gamut of art’s creative endeavour. Both are attained by the way of love, which I define as self-loss in reciprocation with that which is loved, be it the unknown God or the as yet unrealised work of art. Both are caught up by the inner spell of love’s wonder. And he or she experiencing the unveiling of the wonder by the artist of that Truth, as viewer, as listener, as reader, is likewise captivated. It is an experience identical in kind, and the marque of humanity.

But religion is the ultimate art form by virtue of the totality of what it aspires to: namely, the probing of that mystery and that paradox inspired by faith: the lovers’ faith in the beloved. Ultimacy is in the title of this talk of mine.

Man takes part in joint worship – church worship, temple worship – as one responding to creative art, under the inspiration of the God-inspired gift in the soul to make such worship. Worship is done in fulfilment of a honed craft, in a mode – let me suggest – like that of Old Simeon in the Temple laying his eyes on the infant Christ, who had entered the world in fulfilment of God’s ‘word’. A person enters worship to share the presence of God, as Truth – share it, bereft of self (as Simeon saw himself at his life’s finality), devoid – at this point – of the activity of thought, devoid even of emotion (in the sense of further motion), having given way now in abandonment only to transcendent peace and joy (the joy/grief of Handel’s tears), in thanksgiving. Here is earth-bound Man at the apogee of Now, of Timelessness; the self at its apogee of selflessness; the worshipper in one-ness with the worshipped.

Which of us who creates has not known something of this, in the throes of creative inspiration, the probing and expressing rewarded by what descends upon him or her. There is no comparable exhilaration save that of reciprocated love in the very act of it: for it is the same self-loss at work in the soul, the willing sacrifice of the vaunted self in its act of surrender and abandonment to the relationship we know as love. This is the ‘divine frenzy’ written of and surely known by Plato, that awaits every creative spirit on our planet, and known of from the dawn of the human story from the Palaeolithic Man of the Lascaux caves. It is why, to this day, the artist, the poet, the musician, is instinctively a figure to be honoured in society, to be given the benefit of any doubt of authenticity. For they may be seen to be responding to the secret magnificence of their impending self-sacrifice in an act of response to the love God-given by inspiration… or to be so attempting. The apt word is vocation.

Yet things are different today, oh yes, from what they were in the day of Jesus, when so much of Man’s life on earth was lived beholden to the Ultimate, to the God of (in a later definition) The Cloud of Unknowing. The mind-set of antiquity had prevailed throughout the world, be it in the jungle, in the temple of the Hindu, the stupa of the Buddhist, the shrine of the Zoroastrian, the cabals of Gnostic or Essene, the temple and forum of the ancient Greek and Roman. Mankind everywhere was beholden to deity. So it remained. It informed the emergence of alternative or skewed versions of Semitic or gnostic wisdom as in Manichaeism (third century) or Islam (sixth), more recently Mormonism – Islam, which, to be fair, was to evoke a spirit-driven flowering of architectural art and ceramic art, and such poetry as that of Hafiz or Rumi.

Christianity succeeded in holding intact (not without trouble!) in those critical formative early centuries, acknowledging certain spiritual explorations of the neo-Platonists and the Greek philosophers, holding fast enough to the purity of Christ’s teachings in the apostolic tradition.

What stayed proved its truth, through the Dark Ages and the flowering of medieval Europe with its wondrous cathedrals, the supreme witness of its saints and preachers recorded in poems, prayers, sermons and exhortations.

Christianity had become rooted as the universal religion of the Roman Empire and what succeeded it, from the entire littoral of the Mediterranean across all of continental Europe and its islands (us), much of which had emerged from inchoate paganism. What accounted for this wildly improbable phenomenon, of this virtually unchallenged authority upon the minds and hearts of these our ancestors? I again contend, it was the Truth: it bore upon them as a Truth that engendered, in those minds and hearts, joy and wonder and peace. By the elevation of the principle of Love at the heart of the mystery of the gift of creation and Man’s presence within it, probing and art-expressing Man had his clue, his key there among the remote location of Hebrew Palestine. It had lain concealed, in waiting, now to be revealed in the figure of this all but obliterated itinerant preacher-healer, half-casually condemned to ignominious execution for the sake for a bit of colonial peace, who came back to life – to the amazement of his bewildered followers – to be recognised, by the sacrifice of himself in an act of love on behalf of Man, as God incarnate.

The function of Man, the conscious Being – Being as consciousness – was now and forever self-abandonment in union, in love, as in Jesus, thus transcending flesh and blood, time and space.

By this self-loss, the supreme gift – the gift of life – makes sense; receives its justification. Do we not know this – each one of us here – how in the expression of any relationship of true love, all is well (‘all manner of things is well’), the very purpose of Being is met… in ‘time’ and, yes, out of time.

It is the identical experience in the act of creativity on the part of the artist: the fire of inspiration, its joy, its ‘justification’, ‘truth’; the point, sense, purpose of the gift of being… and, by reflection, on the part of the experiencer. Note the analogy of fire: the flame, the intensity of light, of heat – the transformation of matter of one kind into another; how we live daily in the experience of such metaphor, be it in love, in response to beauty, in joy however manifested. This is the oscillation of soul and body within the singleness of Being.

Hence, the way to possession is by the way of dispossession.

To justify this gift of being has been from the beginning the core preoccupation and the supreme attainment of evolution on our planet earth: namely, Man, the creature man. Certainly he must strive and multiply: to find his food, his shelter, his mate for reproduction. But just such has been the immemorial function of the entire gamut of lesser creatures. To categorise Man’s function as such, which is what economists are self-condemned to do and many a politician, dialectical or otherwise, is essentially to misread Man, essentially and insultingly, since it classifies Man as not essentially differing from any beast or earwig.

Man cannot but recognise his deeper or pervasive cause for being what he is. He must strive to worship in the context of religion.

To the worshipper and the creative artist the experience of self has brought, and ever brings, the reward of joy; the joyful catharsis of fulfilment by the act of sacrifice I have touched on. To the religious, what is at work is named Grace, the Grace of God, and from the mystery source: the whole, the Holy. This is the foreshadowed allure for the man of prayer, the painter at his easel, the composer at his keyboard or his staved paper. Man must reach, must explore, must essay; and if there is that to be learned, learn. Read, and mark; then digest, inwardly. He can never stand still, never say: ‘This is it, I have reached destination, my paradise, apotheosis.’

Why? Because he will be forever grounded by the urges required for survival; to eat, to make love; and for these he must always compete. Yet the primal urges are in themselves part of the pact of holiness (wholeness), and the essentially intuitive, unaware contribution, which may be savage, imperious, and spontaneous in the allure – as of that fruit (apple), and in love expressed in spirit or in body, undeniable in rightness (aka Truth).

Hence we make our laws, load ourselves with rituals and moralities, management and forms; rankings; theories; earthly powers and politics. Yet to engage in love we strip off, we dismantle; to eat we pluck and grab and slaughter; and to worship (for we have discerned our claim on divinity) we make fire (for bread, for sacrifice), we invoke the principle of inebriation (wine), we summon light (in that most feminine and perilous of form, the candle flame) and make of that most irreducible material, stone, the most primitive possible edifice, the altar, declaring its sanctity.

Now, up to the close of what we now call the Middle Ages, the paramountcy of the divine in the community of Christendom – and no less so beyond it – prevailed as the soul’s natural condition as it had immemorially. Then we began to lose the plot. The paramountcy of the divine mystery was rivalled: the dualistic heresy (the word means choice) was taking shape, most famously exemplified by the figure of Descartes, still seen as the father of modern philosophy, in the early 17th century. Self-loss was to give way to its reverse, to the ego (in the coin of the Viennese psychiatrists), to self-aggrandisement, to what we have heard termed (by William James) the bitch-goddess Success, the exploitation of fame. Art for Art’s sake was to rise as legitimate endeavour, to our lasting cost. We have the Turner Prize, travestying the painter’s name. The authority of true creative endeavour might not be extinguished, but it could be and has been shrouded.

The soul will out, however, as I am often reminding sisters and brothers, and to illustrate this vital reality as to the sacred unity of art and the Holy, I will cite two instances, once again from music. Which of us does not revere Beethoven as a sublime exponent of musical inspiration (a precisely spiritual term I have this evening repeatedly employed)? So he is, yet how enhanced is that master in his sublime faculty by his deafness and our own awe of his genius by the defiance we know of in his Heiligenstadt Testament of 1802, when facing – aged 30 – the ineluctable withdrawal of his faculty to hear.

And as for the second instance, what of our recognition today of the supreme achievement of Franz Schubert’s final song cycle Winterreise? Schubert was confronting death, weeks away, at 31 from the mortal syphilis he had know of for the previous seven years. In those seven years he had poured forth countless works which he knew he could never live to hear performed or witness their redounding to his honour. Ponder this, my friends, in the context of true art, of oneness with the self-loss of love in reciprocation to the love of God, life’s giver (Meister Eckhart used to say, if you offer no prayer but thanks, it is enough).

And, musically once more, let us place alongside in our mental ears the wordless theology, or theophany, of Bach’s purely instrumental compositions; his partitas, his organ preludes like that in G, BV568, which Andrew our musical director gave us here at St George’s the other Sunday morning. Of course I could go on; and so could all of you.

Here at our Sunday worship we preface the gospel reading with a quotation of Deuteronomy, which Jesus himself was prone to quote, ‘Man does not live by bread alone but by every word that comes from the mouth of God’. This ‘Word’ is not as it is spoken, not a sound; rather it is ‘truth in enactment’ and in the enactment recognisable in Man. It is heard in the soul (in the Jewish religion the creed is called the Shema, ‘the hear’). The Word is the ‘core truth’, God’s truth, and from it spins off expressions of that Truth in myriad manifestations – or better; the core Truth is as it were a gemstone, a diamond of myriad facets which, being turned by the mind of Man or by the heart of Man casts itself (its core truth) in myriad ways. By the modern mind, each facet may be dubbed a ‘metaphor’ of the Word/Truth as, for instance, where the passion of love between man and women in the Song of Songs may be cast as metaphor of mankind’s self-abandonment in response in the embrace of God.

And yet such seeing or hearing or living of the faceted ‘word’ does not diminish the actuality of the eternal Word because of the modern mind casting it as a metaphor in the form of poetry or music or picture or physical beauty or artistic creativity in whatever mode. It is the ‘Word’ that comes from the mouth of God. And does God have a ‘mouth’? Come on, I protest: we are only human, an articulating mammal species, a ‘forked beast ‘, strutting our stage, ‘such stuff are dreams are made on and rounded with a sleep’, doing our best with the vocabulary life has provided for us physical survival and wellbeing. Let us not blame ourselves – though we often do – for the limitations of our mortality. We have been touched by the hand of the Divine, we do our erratic best (kyrie eleison); we make art, we make religion.

We make art in all the ways I have described – in myriad forms, invent our myths and stories so vividly they assume reality; make and enact our dramas, re-casting in contained form shaped for actors and assimilable by the rest of us; we make buildings to defy the passage of time, not only by the presumption of indestructability but by a Truth embedded in their design; and we – wait for it – make worship by any means I have described (prayer, praise, lamentation, thanksgiving), render in every such endeavour that which we venerate, which speaks of Truth we cannot but forever postulate and claim, by every means we are endowed with, through our allegiance and potential one-ness with. Such is that ‘every word which comes from the mouth of God’. And without that Word indeed, with bread, we cannot live if we are declarable as Man.

Have I not been arguing that art in its true creative integrity is part and parcel with that Word from which stems our faith? So I have endeavoured?

The title of our current series of talk here at St George’s is the ‘exploring of faith through art’. My title is Religion as the Ultimate Art Form. Faith and Religion, you will have observed, are not the same. Religion in my lexicon means the objectivising of Faith; it is the collectivisation of Faith, Faith as dogma, rules, rituals and regalia, Faith organised by men – which men, maybe on their knees, maybe inspired by what they have heard in the heart, that Word, received as Faith, one with one, in the closet, or on the mountain top, or in the desert, or the cave depth where there is no light but the moss lamp. Meister Eckhart would speak insistently of the continuous ‘birth of God in the soul’, and would extend that metaphor. Do you not share with me how the conception of our faith as Christians is analogous to the conception of human life – in the caprice of it – the happenstance, the secrecy of it, the mute intimacy, the darkness of it, the hazard of its fertilisation, the implausibility of its survival? Faith is of the soul, the soul’s stance. It has no substance in time and space. It is but of that theoretic instant of conception.

We of the dominant culture of the global village are living in unnatural times. The professional creative spirit of today is not aware of the divine spark in the soul, but is reared in corruption. That spark of conception (Vünkelin), which provoked in Mary her song of thanksgiving, was to have to bear the one that would die in agony for the corruptibility of Man. The natural mindset of Jesus and his Judaic legacy is hidden from us of today – that mindset by which we could lose our self in our experience of love in response to given Love flowing forth from all that is, seen and unseen – the material world in all its splendour and invention, and the mystery of materiality’s infinite and eternal provenance: alas it is shrouded from us.

But we here in this church here tonight note how the Christian faith will not go away. Here it is, all around us, vouchsafed supremely in our worship here and in our Christian churches, and in the religious art and matrix of historical narrative, mythology, hearsay, prophecy and inherited wisdom expressed in poetry and prose, and in countless interpretations of the life and death and resurrection of its catalytic figure surnamed Love, Jesus of Nazareth, as defined by prayerful Man and refined over time by the scholarly and the creatively inspired devout in that great panoply of all true art. This is our God-given endowment.

© Tom Stacey, 2016