You are never so much yourself

as when you lose yourself.

Lecture at St George’s Church,

Campden Hill, on 30 October 2018

I have brought you here under false pretences. The title of this series is Exploring Faith Through the Arts. But what I intend to do is re-define Faith and re-define Art … and perhaps thereby (and by God’s grace) discern what is taking place between these two fundamental realities. I shall project for you no pictures (though I shall refer to some which are already familiar of have been made familiar by the valuable talks we have had so far). I shall be quoting passages from certain writers and from Scripture. But I don’t want to hang this talk on visual or verbal or aural samples of art from art’s vast panoply but, rather, keep upon the plane of ideas, of theological and philosophic perception.

That was the plane of a talk I gave to friends here at St George’s a year or more ago, on the theme of ‘Religion as the Ultimate Art Form’, offered when we were in the same intellectual and spiritual space of Art and Religion, and later published as an article in Standpoint some may recall as A Letter to My Great-Grandchildren. In that essay I was not reducing faith to an artistic endeavour but, rather, raising art to the plane of faith. This evening’s talk will take that theme, that perception, further. This time I am talking about the Divine and Man-as-artist, and similarly I shall not be shrinking what we name as God in relation to inventive Man but raising inventive Man to exposure to the truth of the Divine. Meanwhile, a novel of mine has been published, A Dark and Stormy Night, which as some of you have already discovered implicitly entwines Body and Soul.

Tonight may be demanding a lot from you, straight into the ear.

May I begin, if I dare, by tracing the trajectory of the soul.

What is soul?

I have come to remark to my agnog descendants, the fashionable-minded ones, ‘My dear, like you, I do not believe we have a soul.’

I pause.

They regard this church-goer. I resume.

‘No, we don’t each have a soul. We each are soul.’

And, supposing I still have the attention of this one or that one, I will venture on. ‘Soul is an interpretation of who we are. A reading of each one of us.’

‘A reading?’ I detect a query.

Soul is that reading of us which places us in relation to the eternal and the infinite – that is, in the presence of the great mystery of how we mortals in space and temporality have come to be; of how all this evident materiality has come to be.’ My arms open to the scene around.

Soul, then, is us interpreted in the Latinised concept sub specie aeternitatis– under the eye of eternity. Soul is us who exist placed in relationship with, even in the presence of, God, who does not ‘exist’ but, rather, pre-exists. God is not a thing among others things. God is a Man-coined word for the inexpressible. The first Hebrews, in their religious inspiration, had him say of himself, ‘I am that which I am ’ – the perpetual now, whose polar twin is the eternal.

Out of that nothingness – that no-thing-ness – have we come: as flesh and blood, a person, a thing among other things, life among other lives, and to that no-thing-ness we shall return, ‘for good’ as our language interestingly has it.

And the purpose of any life must be, in logic, to bring us, with our unique and Godlike gift of awareness of our mortality – our dimensionality – which is to say our Consciousness, to that understanding whose ‘purpose’ has been superseded. For we shall be reconciled to the further Truth of No-thing-ness, the presence of God, the great Unseen.

We Christians postulate eternal rest in peace. Requiem, we say, and sing. Some postulate a halfway-house of Purgatory or Hell, and a door to Paradise: I won’t argue.

Yet something amazing has occurred in the gift of life to our species of that awareness. Here is, confronting us, the unique, unprecedented and inestimable gift, the love of this God, the overwhelming love, which is present in its recognition by us, in its infinite potential –poised realisation, as a quantum physicist might regard it.

We humans, homo sapiens, uniquely, are at that juncture of the Seen and the Unseen (in the vocabulary of our Creed). And we know ourselves to be at that juncture. By an intuition that is not less than overwhelming we, conscious of where we stand, see ourselves as inheritors of the Unseen, beholden to the Unseen.

So globally, and since ever, we have moulded our religions. As the French philosopher at Cambridge at the turn of the last century, the esteemed Henri Bergson, put it, humanity is ‘a machine for the making of gods, the essential function of the universe’ – whimpering, ‘half crushed under the weight of the progress it has made,’ straining and pleading for the reconciliation with the non-dimensional, the reconciliation of space-time with the infinite-eternal, the Seen with the Unseen.

This cannot but be our role.

It is exemplified, let us be aware – that reconciliation – by the universe itself. For the universe is simultaneously of the dimensional and the non-dimensional: of space and time, which conscious man is ever more adept at probing and measuring, and of the immeasurable.

Man alone, with his unique gift of consciousness, of sharing the ultimate I Am That I Am (Exodus 3:14) which our spiritual ancestors, the first Hebrews, heard ‘in the mouth of God’, is presented with the utter wonder at where he stands in the order of creation, the conscious recipient of divine creational love.

Now let me say a word on the phenomenon of Man, which is You and Me.

In our day and age, in the era of Martin Rees, Astronomer royal, and the pin-up physicist, Brian Cox, we are ever more cognisant of the immensity of the universe. We are informed of the events or cosmic situation of so many light years distant or indeed hundreds of light years distant: information, therefore, which has taken vast periods of time to reach us at the speed of light. We know of galaxies and solar systems with a comparable scatter of planets, even of an occasional planet rotating a star which conceivably could support what we know as life in some form, even if no more than microbial.

With the vast and expanding range of our investigative compass we postulate the occurrence of conditions enabling life, even intelligent life – which is to say of a conscious species, comparable to our own, although far more probably well short of consciousness. Just in case, we have dispatched into outer space capsules containing clues for our fellows in the universe – with fragmentary evidence of our civilisation.

It is hard not to sense the absurdity of all this. We cannot talk of the ‘immensity’ of the universe since immensity is a spatial concept with no meaning in the context of infinity, of spacelessness.

Yet suddenly (euphues, as the evangelist Mark might exclaim) into this non-dimensionality – this infinity, this eternity – there appears a conscious being with the gift to perceive the amazing uniqueness of his presence on the material plane of dimensionality, of time and space: suddenly, in days, this evolving ape, homo erectus, becomes homo sapiens. He and his lady eat the apple of the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil. Both cover up. He hears the voice of the deity he has postulated, who demands of him Who told thee thou wast naked?

He discovers You, he discovers I (in that order, if I have read with precision my children in their infancy). He can identify with another’s pain, respond to another’s love. He can recognise that he is made in the image of the progenitor of all there is and can ever have been or can come to be – of the Seen and Unseen. He names the Mystery God and hallows the name, and by virtue of his astonishing gift of life, in awe and trembling, loves what he named as recipient of his [Man’s] love; and by virtue of what this mysterious God has bestowed on him, perceives himself made dimensionally in the image of the non-dimensional God to – what? – to live out a life for a few decades on what modern science cannot but classify as a single time-tagged planet circuiting within a particular solar system of exquisitely calibrated gravitational forces, belonging to a particular galaxy amid galaxies without number, any or all of which are transmutable by the deforming of space-time as Black Holes.

OMG.

But hold fast!

Mankind cannot but recognise himself as an inheritor of a gift which is unique in the universe, a source of enduring astonishment and an implication of sublime responsibility.

Such responsibility, surely, we have: You and I, here and now, we alone in all creation, that which cannot but recognise the magnitude of our inheritance. It has come upon us by the intervening hand of the unidentifiable authority we have named; or possibly by an evolutionary fluke; or just possibly by capricious experimentation on the part of a divine authority such as toyed with Job.

Whatever is the truth of that, we the human race cannot but occupy the most significant dimensional role in the created universe. This is a reality we can hardly refute, and a responsibility we can hardly pass up.Who on earth are we, then? How come the paradoxical title I chose for this talk, which I lobbed back by email to Father James more or less spontaneously when he invite me to contribute to this series? – You are never so much yourself as when you lose yourself.

Let me hold in view my self-commissioned brief.

And hence be reminded of the seemingly ruthless injunction of the founder of our religion on the matter of self-loss. All four evangelists quote Our Lord, each in his own style. The fullest declaration is that given by Mark [8:35].

For those who want to save their lives will lose it, and those who lose their lives for my sake, and for the sake of the gospel, will save it.

That quotation reflects, of course, the very first beatitude, that first among the blessed are the ‘poor in spirit’, who have come to count themselves as negligible, yet ‘whose is the Kingdom of Heaven’. Here we are at the core of the gospel.

So to meet my brief I must look back to the origin of all religions from the beginning of consciousness. The Holy Bible does likewise. Be clear, my friends: I am in accord with the Hebraic-Christian tradition or, dare I say it, exploration. Such determines my chosen faith and is the focus and the context of my worship.

Faith, I venture, is not a static attribute, a fait accompli, an idée fixe. It is a continual exercise, a daily rebirth. There is no faith in any person without the capacity to doubt, rather as there would be no conceptual awareness of Life – to Man’s consciousness – without evidence to him of Death. What does that unsurpassed preacher, administrator, and mystic Meister Eckhart, of whom it has been said ‘God hid nothing’, who died in 1327, say of Faith, which he calls ‘a power in the soul’? Let me quote from his German sermon 66 in the Walshe translation:

‘It does not grasp God when it first emerges insofar as he is good, nor does it grasp God insofar has he is Truth. It delves deep, ceaselessly seeking, and grasps God in his unity and his desert. It grasps God in his wilderness and in his own ground… When the Soul receives a kiss from the Godhead, that Soul stands in absolute perfection.’

That is, in that Unity.

To such a concept of self-abandonment I hope to return before I am done tonight.

In my own venturesome and eventful life I have encountered and participated in religion in a multiplicity of forms and structures of belief, fancy, supposition, superstition, and ritual, and in religions stemming from human communities and human experience at various stages of social evolution. I had just turned 20 when I found myself participating, in the heart of what we now call the rainforest in north-eastern Kelantan, on the then seldom penetrated Malaysian borderland with Thailand, in a nocturnal shamanistic shuffling dance and incantation to the beat of a bamboo by a hunter-gatherer community of Temiar aborigines, whose entire world was interminable rainforest.

Four years later I was to encounter in matching circumstances of equivalently pre-metal Man the Bambuti pygmies of Eastern Congo; then for months on end I shared the lives of their Bantu neighbours, cultivators, still virtually untouched by any colonial hand, on the Ruwenzori mountains. I have subsequently lived in trusting comradeship with Muslims in the all-desert environment of Arabia. It was from their Bedouin territory in which Islam irrupted some six centuries afterthe vividly more refined ministry of Jesus of Nazareth 2000 miles to the North on the fertile east Mediterranean littoral. These committed Muslims were surely devoted to me, as I to them, yet mourned, truly mourned, my irredeemable exclusion from their awaiting Quranicly-assured Paradise as the Christian infidel that I was … and remain.

Even today, right now, at an intellectual level, I am engaged with a group of others I esteem, including devout Hindus, in a study course in the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali – at fortnightly intervals in Upper Addison Gardens.

My hunter-gatherer friends’ notions and devotions do not bear upon the world of modern man beyond. The beliefs and precepts of Muslims and Hindus and related Buddhists, however, command the convictions and guide the actions of millions upon millions of our fellows in the world of today.

All of today’s prevailing faiths arise from that challenge of Man’s confrontation with the mystery of his mortal origin on the finite planet Earth, in a universe of eternity and infinity. However, the civilisation and culture arising from one particular religious tradition, may be seen to have taken precedence across the continents in public ethical, political and judicial methodology has one persuasive explanation: that it carries within it a spiritual authority instinctively recognisable as a revelation of truth. That religious tradition is ours, Christian.

Christianity preaches Incarnation: that is, the presence in the flesh on terrestrial Earth of one divinely anointed, the Christ. Out of the mélange and amalgam of myth, metaphor and analogy, of hard historicity, reportage and oral tradition, and of spiritual experience, all of which contribute which contribute to our planet’s extant religions, arises this Christian phenomenon. It draws from the well of Jewish culture and religious insight the astonishing figure of Jesus, from his carpenter’s workshop of negligible Nazareth.

Hail the straddler of the dimensional and the non-dimensional, who died to rise – who sacrificed an earthly life to the cold secularity of high priestly power and politics to reclaim life in eternity. Christ uniquely vaulted the frontier dividing the See and Unseen.

Was this vaulting, dear friends, for real? For what constitutes the realin the context of soul? In their reports of the resurrection, we note the evangelists Matthew, Luke and John taking pains to intrude a factor of the surreal in what they describe of the risen Christ. He enters the upper room through a shut door, he vanishes on the breaking of bread at table Emmaus; he was, more than once, either mistaken for somebody else, as by Mary Magdalene in the sepulchre’s garden, or was first unrecognised, as by his Galilean apostles who had hastened back to the lake that gave them their assured living.

We are being given pointers.

In his book entitled Resurrection, Rowan Williams writes of the ‘apparitions’, a term which allows for modification of earthly reality – for, let us say, in alternative terms available today, of hallucination or auto-suggestion. Yet we are biblically assured this ‘apparition’ required to eat. We are assured this tomb was empty of any corpse. And Paul, or more precisely Saul, whose conversion was not by the visible reappearance of Jesus but a blinding light and the Christly voice, has solemnly averred in 1 Corinthians 15 that ‘if Christ be not risen then our preaching is in vain and your faith is also vain.’ This we place in the verifiably historical context of what Paul did with his life after that Damascene event; and no less what other recorded witnesses of the risen Christ did – Peter, John, and Thomas of the Upper Room – did with their lives thereafter.

Who can determine what today’s mindset requires to define ‘reality’? Who knows what became of the unrecorded witnesses of the post-crucifixion physical Jesus? C G Jung, the towering pioneer of psychological medicine, is quite content to write of psychic reality, the Greek psyche meaning soul.

What unquestionably occurred was a vivid sense of the resumed presence of the Christ, the anointed one, in the midst of his followers, most vividly perhaps in that upper room where the Eleven may have been prompted by rumour of the vacated tomb to break bread in memory of their crucified Lord. Or again, we may suppose, among those Galilean fishermen back at their trade to feed their families, half in despair, half in wonder. Or again in the exhilaration of Pentecost.

We might dare speak of a numinous presence of virtual palpability, inspired by Jesus’ promise of his perpetual, timeless presence among all his followers, which was a recurrent theme of his teachings.

The capacity in Man-as-soul to engage with the revered Mystery since consciousness broke upon us is everywhere and incontrovertibly attested by saints, martyrs, and mystics of the Christian era, no less than by the Jewish prophets and sages of the Old Testament … attested down the ages by any or all of us in prayer, in worship, in contemplation, in self-denial and self-emptying (kenosis), and – wait for it – in Art: the creating of Art, in responding to it.

Man in his sophistication has delved for the vocabulary to fit that engagement, and brought up such terms as Soul, the Grace of God, the Word, indeed the very name which in English we sound as God, a term of Teutonic origin, strictly non-personal, meaning that which is worshipped, invoked: i.e. the awaiting blank space. We have been driven immemorially to feed the engagement, feed what we have chosen to believe: the music, the poetry, the visual images, the spires, the craftsmanship doneinawe and devotion.

Incontrovertibly Jesus of Nazareth was crucified, his body, apparently lifeless, prepared for burial, disappeared; the notion of his reappearance was given credence, and all this – endorsed by his self-prophecy – opened his followers to an astonishing narrative, I daresay metaphor, of humankind’s engagement with, and allegiance to, the Fatherhood deity.

The incarnational idea won its narrative, its parable, and so won its truthfulness. The life, death, and resurrection of this Jesus was itself revealed as a work of artworthy of reverence forever. Man-as-Soul, servants of God, thus inspired, made sure of the vision granted by that single event in Palestine. This Jesus, whose appellation as the Son of God had been offered to him in his lifetime in contrast to his own self-appellation Son of Man, was to be doctrinally honed, refined and endorsed in his Trinitarian unity in the succeeding two or three centuries. Christians in their collective wisdom entrusted that endorsement to the Church of Rome as its Faith, such as could offer ever thereafter redemption to its adherents and believers.

Out of those fragments of historicity, of oral and written record, of spiritual experience, and the treasure of its founder’s and his followers’ teaching, Man had fashioned a religion. It was itself, as is all religion, an ultimate art form.

Please hear me say: the artificer of all religions cannot be other than Man himself, shaping out of what clues are vouchsafed by the explorers of Man-as-Soul (that is, by those of such spiritual elevation as to have entered the presence of what I’ve called the Mystery, piercing the Cloud of Unknowing). These explorers are such as us, seeking to live a spiritual life, cleansing the thought of our heart by the inspiration of the Wholing Spirit, informed by the spiritual persuasiveness of the gospel, the Word, inviting worship, and perceiving in all the hand of the Divine.

We are not alone in the story of mankind. Such it is with the Baghavad Gita and Upanishads … and surely the Patanjali Sutras of Hinduism I am currently learning of; such with the narratives of Krishna and Arjuna and the Mahabharata and the multiplicities of Hindu deities and the saddhu’s mortifications; such with Buddhism, in its Malayalam and Hinayana formulations, or indeed the Tao; and no less with the other, non-Christian, Abramic religions of Judaism and Islam. We Christians do not boast exclusivity of Truth, yet note when rootedly we differ. From both Jews and Muslims, for instance, whose established doctrine binds them to vengeance: lex talionis, eye for eye, tooth for tooth. Or, more subtly, from the Buddhists, appropriately revering their avatar Gautama who, when asked if compassion was due to the suffering of others, paused before replying There are no others. The power of spontaneous healing may indeed have been vested in such as himself; yet the rest of us, devoid of such Christlike a gift, were enjoined no hands-on charitable activity such has characterised the humanism of Christianity from its beginning.

Biblical Judaism we Christians cannot but honour, first for its founding vision of the single immortal, invisible, omnipotent deity – in his exclusive revelation to and guardianship of the chosen ethnicity, such as defined him and won his recognition, demanding his love, his moral obedience, in reciprocity with his people’s allegiance. It is enshrined in prose and poetry by the hand of David, Isaiah, whoever authored The Song of Songs, Jeremiah, Daniel and more. And we honour Judaism for foretelling – in passages leaping from its texts with uncanny precision – the coming Messiah we know as Christ.

Yet we Christians should not be shy to share with subsequent, post-crucifixion Judaism down the millennia through the Kabbalah and such as Maimonides, Israel ben Eliezer of Hasidism to, say, Martin Buber of our own era.As for Islam with its Prophet, his Quranic book of rules substantially derived from half-heard Jewish scripture and narrative, it has attained to spiritual eminence only as Sufism, exemplified by such as Ibn al-Arabi, Jallal Uddin Rumi and Farid Uddin al-Attar in poetry, prose and dance, and celebrated in glorious architecture and the decorative arts – yet all such attainment, being Sufic and Shi-ite, catastrophically outlawed by mainstream Sunni Islam today.

Ourselves, meanwhile, we of Christianity, inherited pre-Roman Judaism by the hand of our founder Jesus who came in his own perception to ‘fulfil the law and the prophets’. He was to teach all but exclusively by parable, yet – I put it to you –implicitly and supremely by the very parable of his own presence on Earth: his conception, birth, and life and death by judicial murder … and reappearance – a figure of unchallengeable purity and seemingly unprecedented powers. He was willing to lose his life ‘for us’; which is to say, to redeem the human race, buy it backfrom its self-bound secularity to the spiritual responsibility of self-denial to which I argue we are inescapably heirs.

Parable was Jesus’ chosen vehicle of imparting truth; and his own life, as he recognised in its scripture-endorsed fulfilment, was the supreme unfolding parable, that ultimately persuasive art form of our Faith. As I have said, this very Faith is, significantly, what has come to shape our modern world’s overriding precept – whether credited as such or not – in governance, law, morality and aspiration.

What, then, am I saying?

A parable is a piece of fiction: in the mouth of Jesus, a mini work-of-art, a ‘fiction’, the word meaning ‘shaping’ of which Man is the shaper, the artificer. It reveals a truth. Jesus telling of the prodigal son or the good Samaritan is unfolding a truth. Jesus’ life as interpreted by his disciples among whom we count ourselves, is a parable transmitting a truth to be known inwardly, beyond words. An entire religion, as I contended a year or so ago, is a form of art.

Since you allowed me that then, I am asking you now to allow me more.

We have conceded that we are living spiritually (that is, at our deepest level and on our highest plane) by metaphor, parable, allegory, interpretation, all stemming from the mind of Man or (better still) from Man-as-soul, through an urgency of will which is instinctive, intuitive and imperative. Man-as-soul knows himself and all that is, the Seen, as sanctified, of divine origin, sub specie aeternitatis, created over against the eternal and infinite, the Unseen.

That is quite a paragraph, quite a demand before your supper.

What I am characterising as ‘metaphorising’ in Man’s subjective experience of the world he is born into, a devout Buddhist would take further, and declare – as you know of Buddhists – all terrestrial, dimensional experience to be ‘illusion’.

Whatever the nature of his response, the species Man is the key artificer, the ingenious genius. Hence, my friends, does he make Art in its common definition and form, in speech and writing and song, music of every mode, movement, fabrication and craftsmanship, from his entire range of perception and capability. So he has done ever since his first accession to the title of sapiensin the nether parietal shrines of his Mesolithic caves.

Across all the religions we at once encounter an interchangeability of ideas, intuitions, goals and methods, a patent parallelism.

No thing is exempt from Man’s interpretive spirit at work, by characteristic metaphor. Metaphor – symbol, simile, analogy – releases the focused object from itself, liberates it into its universality: that universality where all is to be acknowledged as the work of the Divine.

Atmospheric vapour in chance formations with a strong light behind it: what is that? It is a sunset, brothers and sisters, in its mesmeric glory!

Let us now be unafraid to ascribe to our Mystery, the clouded Unknowing, the title Divine.

My A Dark and Stormy Night here on the table is I hope a compelling story. My secret intention in writing it has been to recognise in Man-as-Soul the entire gamut of what he encounters in life. My narrative concerns love in the heart of Man – a particular fellow whose capacity for love spans (like most of us) the sacred to the profane; the full sweep. The ‘profanity’ means the act of love between woman and man and the working of desire, without which event not one of us would be here. My fictional protagonist, a scholar of Dante and lately bishop, in the flush of life, allows himself to admit to lust ‘that there may be love’. For he finds at the core of love in all its intensities an authentic loss of self, a readiness for sacrifice, the elevation of wonder, a universal joy, a banishing of fear: that very same readiness, in its context, of our patron George to respond to his ultimate love and dare despatch his dragon.

In such ardency a lover’s life, the self, becomes of nothing worth. He has let go of himself, no less she of herself, the infamous ego, yet is now transcended, never so much himself or herself. The criterion of the first beatitude concerning self-negation has been met: that he who is ‘poor in spirit’ is now, astonishingly, on the threshold of ‘the kingdom of heaven’.

Yet – and please stay with me – all that is within Man’s cognisance is of Divine creation, is it not. And so it falls to Man to find in all that he can touch and see and hear and scent that in which the hand of the Divine is conjurable within him: the presence of the Maker of All Things.

Hence indeed it transpires that we are inwardly spurred to make art, in every form, to enhance that wonder, for us and our fellows so to lose ourselves, to grasp at the beauty and wonder of whatever gift is in our reach or purview, even of pristine nature in stalk, leaf, or panorama. Towards the end of my story in the novel to hand you may read of that joy, wonder, the loss of self.

What is at work is the urge for inner Truth: Truth as Keats defined it – Beauty. Beauty, if I may so gloss the word, being Divinised; sanctified.

So we are to beautify in our minds and hearts all (whether or not by our own hands) – all that we find about us: to seek and find in each perception the Divine Truth of all things, their true being, their Dasein as the philosopher Heidegger would have it, honouring it – as I would have it – as integral to the entire creative gift receivable by Man’s mind, be it that beetle, that leaf, that tolling bell, that distant panorama or that bench of polished wood which Eckhart somewhere cites.

I am asking you tonight to re-define this ‘art’ by which faith may be explored, and its inner and universal truth revealed. It is art in the guise of the unintended, the non-contrived, the art in love, the art in spontaneous recognition of beauty, in sympathy, sharp sympathy, with another’s pain or joy or peace, in whatever it shall be by which we are released from ourselves, our self-preoccupation.

Do you know the poet Wallace Stevens, the patrician new Englander of Hartford, Connecticut? Between the Wars, whatever his day job in insurance, he never ceased to write, rather wonderfully. Stevens had fallen away from the pat Roman Catholicism he inherited with the comment that ‘life’s redemption’ was better met by poetry as ‘life’s essence’ when ‘belief in God has been abandoned’ – the required redeeming, buying back, from the shallow, meretricious, the factitious, the egotistical, that bans soul for (I fear) the generality of folk.

Stevens is the poet of things, the essence of things, which are the waiting stuff of art. Would that I had time to recite you the sea-sky paean The Idea of Order at Key West, where Stevensholidayed; but here he is on the colour green, with me recalling that pale green is often the topaz hue. Stevens entitled it The Candle a Saint

Green is the night, green kindled and apparelled.

It is she that walks among astronomers.

She strides above the rabbit and the cat,

Like a noble figure, out of the sky,

Moving among the sleepers, the men,

Those that lie chanting green is the night.

Green is the night and out of madness woven,

The self-same madness of the astronomers

And of him that sees, beyond the astronomers,

The topaz rabbit and the emerald cat,

That sees above them, that sees rise up above them,

The noble figure, the essential shadow,

Moving and being, the image at its source,

The abstract, the archaic queen. Green is the night.

You may have picked up the Christian slants there, and the vast irrelevance of outer space as outer space of which I have spoken.

There is no thing which, in the sight of Man-as-Soul, does not claim sanctity. Jesus said in Matthew10: 29 ‘Are not two sparrows sold for a penny? Yet not one of them will fall to the ground apart from your Father’. Did he not venerate the lily, that toils not nor spins? – and divinise mere water as fit for transubstantiation into wine, and a jar of man-compounded ointment as balm not for body but for Soul. A true man of God, a true woman of God, prays without ceasing, as Paul enjoined his Thessalonian converts – which is to say, never losing sight of the Divine in all things at any time. May you and I not be those Thessalonians?

Rainer Maria Rilke, born 1875, four years ahead of Stevens, was to move to the same perception, the same requirement to us as soul, repeatedly enjoining us, in Edward Snow’s translation from the German:

The traveller doesn’t return to the valley from the mountainside

with a handful of sod, round which all stand mute,

but with a word he has won, a pure word, the yellow and blue

gentian. What if we were only here to say: house,

bridge, fountain, gate, jug, fruit tree, window, –

at most: column, tower … but for saying, understand,

oh for such saying as the things themselves

never dreamt so intensely to be. Isn’t this the secret purpose

of the reticent earth, when it urges lovers on:

that in their passion each single thing should know ecstasy?

O Threshold: what must it mean for two lovers

To have you for their own, their own older threshold, and be wearing down

A little of your ancient sill – , they too, after the many before,

Before the many to come …

Earlier this month in Oslo I visited the museum containing two ships of the Viking era dating from a millennium or more ago now restored and reassembled to perilously fragile perfection: meticulously crafted and exquisitely carved oaken vessels, open to the sky, 70 feet long, which had braved the oceans and owe their preservation by coming to serve as burial chambers back in Norway for the distinguished Viking dead, and by the fluke of the chemical qualities of its embedding clay.

The Vikings’ invasive presence spanned half the globe. They venerated Odin, god of wisdom, power and poetry, and his son Thor, the battle-god. Their boats were not only their vessels, but essentially dwellings, sanctuaries, and (sometimes) in the end burial shrines – Art, I reckon in all dimension and none, fulfilling a role that vividly meets the philosopher Heidegger’s call to Mankind to penetrate and acknowledge the fourfold essence of any human dwelling-space in its union of earth, sky, transcendental divinity and human mortality.

Let us be clear: metaphor is not any substitute for the Truth of anything. It does not mask its truth, not hide it. It enshrinesits Truth. In the business of metaphor Beauty is Truth, and the goal of art.

Now I had no sooner drafted in my head the Viking analogy in my disquisition on the sanctity of all things as interpretable by Man than I was back with my spiritual mentor, Meister Eckhart, born circa1260, to find myself turning up his Middle High German sermon on the text of puella, surge, Luke 8:54. Rise up, little girl (Jairus’ daughter), whom Jesus had restored to life. In Oliver Davies’ translation from Eckhart’s German what do I read? –

‘In the love in which God loves himself, he loves all things.‘

Now I shall say something I have never said before. God delights in himself. In the delight in which God delights in himself, he delights also in all creatures’ [that is, all created things] – ‘not as creatures but in creatures as God. In the delight in which God delights in himself, in that delight he delights in all things.

‘Now pay attention! All creatures tend towards the highest perfection. I ask you to listen to this by the eternal truth, by the everlasting truth and by my soul. I shall again say what I have never said before. God and Godhead’ [gottheit – godhood] ‘are as far apart as heaven and earth. But with God the distance is many thousands of miles greater. That is, God becomes and unbecomes’.

That is, in the light of Man’s recognition of him [this is I speaking, not Eckhart]. For it is us, we alone, the species with the conscious mind, the articulators who need to say God, to give god a name: it is only us who might seek to postulate the immortality of Jesus, his perpetual presence among us, and in so postulating, hold to it. It is within our right. If we have so accorded – that immortal presence which indeed he promised us – such is so.

Let me pick up the Meister in his pulpit a moment longer. ‘Now I return to my original phrase: God delights in himself in all things. The sun casts its light upon all creatures, and whatever it illumines, the sun draws into itself. And yet it suffers no diminution in its own brightness. All creatures are prepared to lose their lives for the sake of their being. All creatures convey themselves to my mind in order that they should exist mentally within me. I alone prepare creatures for God. Just think of what you are all doing!’

Did I not speak of our divine responsibility at the start of this talk? We men and we women, we are the brokers! Between the Seen and the Unseen we of the human race have this overriding function.

What is this I am revealing to you? That all that is, within Man’s cognisance, is of the Divine and, by virtue of our cognisance, in the purview of art as subject to humankind’s interpretation. For that is our function, God-given, our mighty privilege as confessing Christians.

And it is given to the species Man, exclusively in the universe, to refine by further, specific divination as art by his own creative will and inspiration that which is responsive to his gifts and to his urge for the truth of any thing. Hence all that we honour as Art, in music, words, the plastic arts in all their forms, in dance, by the hand, the breath, the voice, the body and the foot [my recurring list], is not of a different order to each and every thing on which the cognisance of the human mind comes to bear with no creative engagement, in our commitment to the Mystery of their Maker’s gift. Allis open to our love, all worthy of our thanksgiving. Every lily, every leaf, alive or dead –all inform – in-form – what we term our Faith, all are to provide a context of self-loss to a lesser or greater degree by which we can enter, selfless, the presence of the Unsayable.

All things in the eye, all experience of Man the beholder, are, in their essence, in their true being, to be honoured and integrated with the gift of Creation in its entirety, feeding by the work of Man’s metaphorising gifts. Nothing in Man’s cognisance is exempt. All is of the Divine accessed by the ever interpreting mind of Man.

Indeed, the driven, gifted person will collude with that Divinity he has acknowledged to make what we name as art – that is, by what we call ‘inspiration’, harnessing spirit, divinely engaged to make a work for the veneration and elevation of others as art in every mode … as a focus of worship, joy, self-loss. As Thomas Traherne put it – ‘You never know the world aright until the sea itself floweth in your veins.’ We men, you and I, are the unique heirs of the wonder of creation to release, liberate all that surrounds us, each and everything into the universal, raising by the working of metaphor, allegory, analogy, extension, juxtaposition and contrast, the Seen into the Unseen through the gift of love in self-surrender.

Ah, love.

Now that is key, the key to the Kingdom, of letting-go of self in union with the Other: that other person, as of flesh or as soul, the other thing as encountered by us as art, as nature’s spontaneous beauty, as divinity, this famous Mystery. In wonder, or enchantment, vision, intensity of concentration, in dream, in trance, in prayer, in creative exhilaration. In, I daresay, ecstasy. Cast about you, see love at work and see in love self-loss – the letting-go of self in transcended realisation with the other. Recall the Song of Songs, recall Juan de Yepes, St John of the Cross, escaping from brutal imprisonment in his Carmelite monastery, to pour forth in a few weeks Spain’s most deathless poetry, recall all-Italy’s unchallengeable Dante lost in his dark wood, to immortalise his beloved Beatrice in La Divina Commedia.

There comes a moment in my A Dark and Stormy Nightwhere my narrator-protagonist, scholar of Dante, is gripped by the truth that ‘the solvent of faith is love, person to person, in the exercise of wonder’ – and also, I am saying now, love for all thingsencountered as awaiting art, all as of spontaneous beauty. Then soon my narrator-protagonist hears the voice of a poet (a poet of my personal acquaintance long ago) Where there is nothing, there is God. To hear that, my fictional quondambishop has himself shrunk to nothing – no thing. Thus is he truly ready for God.

Thus, likewise, the readiness of the Prodigal, stripped of self, to return to his father. You remember the moment, caught by Rembrandt, as the patriarchal hands come to rest upon his lost son’s shoulders?

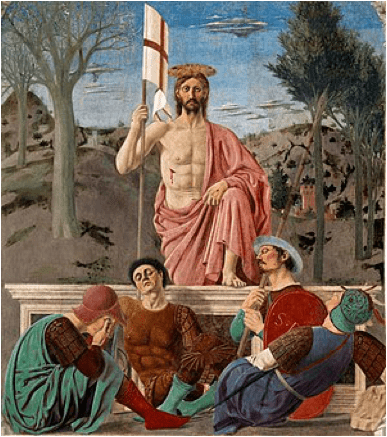

Readiness for the Divine, the presence of God, is no less than the professional requirement of the central character of my narrative. God becomes and unbecomes I have just quoted from Eckhart. Yet no creative artist is truly worthy of his calling who is not convinced of the divinity at work in what he is making, whether consciously discerned or subliminally. When in creativity the conviction of that divinity shines out, we catch our breath, we pause, we bow; we have lost ourselves, transported, be it by this Bruckner symphony, that work by Beethoven, this by Schubert, J S Bach, Byrd, Purcell, Sibelius, God-wary Brahms. You choose: choose your medium, choose your creative spirit; enter San Zaccarias’ church in Venice beside that non-believing Guardian art critic, a certain Tom Lubbock, who found himself kneeling before Bellini’s painting of the baby Jesus lifted up by his mother encircled by saints; choose Piero della Francesca, also brought to us by that brilliant speaker the other evening, Ayla Lepine – Piero to whom Aldous Huxley gave the impossible accolade of the greatest painter ever for his Resurrezione, the overwhelming incarnational statement of our Faith, enshrined in San Sepulcro and saved from destruction in the last War’s triumphant British army sweep into northern Italy by an educated young officer, knowing of the painting’s presence there, and querying an order to shell the place from across the valley.

The incarnational source of our Faith, the factor of divinity, divine love, is in all creation: that we are to grasp, daily and hourly. We know its saving joy and hope. I have spoken too of the redemptive factor, quoting Wallace Stevens, which can stand outside any definable faith: that ‘buying back’ into allegiance at depth with what is Seen and Unseen. But there is this to be noted in our present mood of iconoclastic fervour. When any human gifted with the creative skill and will comes to look only to his own neurosis, his self-obsession, for his source he is set upon a route to despair and self-destruction as Mark Rothko knew or Nicolas de Staël; or to sheer vanity of the Damien Hirsts or Kapoors or Tracey Emins, the artistic stuntmen of whom scripture comments, ‘They will get their rewards.’

Friends, you have been wonderfully patient. I pull my threads together.

Man is unique in all creation as, inescapably, the broker between the Seen and the Unseen.

Such is his responsibility, likewise inescapable: his vocation and his joy.

For he is beholden to that Mystery that none but he, Man, in all the universe, must name, clothe in metaphor, and invoke, as we by God’s grace have been drawn to do in the person of the incarnated Christ.

Man responds to that perceived sanctity of All That Is by recognition of it, and in inspired and crafted worship, veneration and artistry.

To make art is, rightly, to lose yourself in prayer, or praise; to respond to art is, properly, to contemplate or meditate, to lose yourself in contemplation and meditation, and joy.

Thus you let go of yourself, losing that self through the working of love in unifying reciprocity with the Divine reality.

In that self-loss is your true self realised.

© 2018 Tom Stacey